Growing anti-immigration policies, coupled with rising racism and xenophobia in Europe, the Americas, and other destinations, may cause discomfort for migrants abroad — but they could also be a blessing in disguise for their home states. Their skills, entrepreneurial drive, and resilience are desperately needed back home to revive local economies. This is particularly true for Kerala, many other Indian states, and indeed parts of South Asia and Africa.

Across the West, anti-immigration sentiment is no longer fringe politics — it has moved to the mainstream. From stricter visa regimes to reduced work permits, borders are tightening. The ripple effects are global, raising a provocative question: Is globalization entering its twilight years?

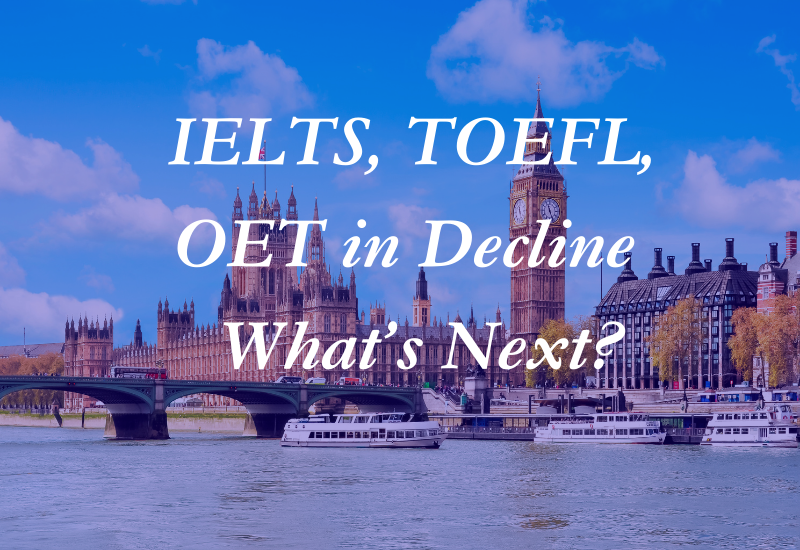

The early signals are clear. Students eager to cross borders for education face growing hurdles. Immigration consultancies that once flourished now struggle. Language tests such as IELTS, TOEFL, and OET are in decline as several countries quietly relax or remove them. The OET, designed for nurses and medical professionals, has been particularly hit. Meanwhile, the brand value of English-speaking nations and their higher education systems faces new challenges. A host of previously overlooked destinations are emerging, highlighting their comparative strengths — from STEM education to affordable opportunities — and challenging the Anglosphere’s long monopoly.

Kerala: A Land of Departure

No state in India embodies the migration story as vividly as Kerala. Unlike Tamil Nadu or Andhra Pradesh, where emigrants are often engineers and technical graduates, Kerala’s outflow is more diverse. Nurses, paramedical staff, schoolteachers, clergy, semi-skilled workers, farmers, and entire families have liquidated assets to pursue life abroad.

This is not new. The Gulf boom of the 1970s cemented Kerala’s role as one of the world’s most consistent exporters of human capital. But the roots stretch deeper: in historical trade, from the spice routes of antiquity to Arab and Jewish trading stations at Muziris, Kerala has been connected to the wider world for millennia. A less industrialised economy, adversarial labour relations, and a politicised business climate have all nudged generations outward.

The Shifting Routes of Migration

Until the late 20th century, migration often followed a staged path — first to Indian metros like Mumbai or Delhi, then to the Gulf, and eventually to the West. By the 1990s, that pattern collapsed. Immigration consultancies mushroomed across Kerala, sending young men and women directly to Canada, New Zealand, and Europe.

Initially concentrated among Syrian Christians, the trend soon spread across all communities. The implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations in the mid-1990s further accelerated this wave. Many in Kerala’s “general” communities felt excluded from opportunities at home, reinforcing a sense of alienation. Though government jobs were already shrinking, the psychological impact was immense. Migration became not just about economics, but about dignity and equal opportunity — if not in India, then abroad.

That dynamic, combined with Kerala’s political climate and the entrenchment of organised rent-seeking groups backed by political elites, made the state an early pioneer of mass migration. Today, similar sentiments are visible across the country.

Ghost Houses, Empty Streets

The consequences at home are stark. Across Kerala’s towns and villages, hundreds of villas stand locked and silent. Grand 3,000–5,000 sq. ft. homes shelter only elderly parents waiting for their children’s brief annual visits.

Take a journey from Vallamkulam on the Tiruvalla–Pathanamthitta road to Mallappally via Kalloopara: this entire stretch looks deserted even in broad daylight. Buses run nearly empty. This is not an isolated phenomenon today. If you lose your way and want to ask someone, you may struggle to find occupied homes or even people on the road for guidance. Delivery boys from nearby towns, even with GPS, often return without reaching their destination, having lost their way. Large swathes of once-vibrant communities now resemble postcard-perfect ghost towns.

Could the Tide Turn?

Ironically, the rising tide of anti-immigration politics abroad might slow Kerala’s exodus. Many families abroad now weigh discrimination, cultural alienation, and high living costs against the comforts they left behind.

One tragic case recently highlighted this. An emigrant Keralite family in the UK lost their child due to a lack of timely medical admission. The grieving father, returning to Kerala for the funeral, remarked: “It would have been much easier for me to secure an admission and the best medical care for my child had I been in Kerala. She would still be alive.” He added that healthcare and other opportunities in Western Europe are often myths — in his view, Kerala and India offered better.

Kerala — still “God’s Own Country” — provides a standard of living and social infrastructure that rivals, and in some respects surpasses, many Western nations. Its hospitals, universities, and community life remain unmatched in much of the world. Yet education in Kerala faces a deeper challenge: it is too often treated merely as a pathway to overseas jobs or migration. This narrow vision limits its true potential as a driver of innovation, entrepreneurship, and local development.

The state also holds immense untapped opportunities. Tourism alone — spanning health and Ayurveda, eco-tourism, and culture — could generate sustainable livelihoods. But realizing this potential requires more than nostalgia. It demands dismantling the very barriers that drove people away: political interference in business, militant labour unionism, and entrenched rent-seeking backed by political patronage.

Complicating matters further, the elites — both political and religious — often benefit from migration. For churches, migration means new parishes, more money, and frequent foreign trips for bishops and priests. For political parties, it means diaspora networks and inflows of funds. For them, a better business climate at home may not always align with their interests.

A Choice for the Future

For those already abroad, the question is blunt: does the dream match reality? Is life in a foreign country — with its higher costs, uncertain security, and open discrimination — truly better than one in Kerala, with its healthcare, education, and cultural rootedness?

Kerala’s empty homes will only light up again when both current migrants and aspiring ones recognise that prosperity does not always require crossing oceans. Sometimes, the brighter future is the one waiting at home.

(Perumal Koshy)

16 August 2025