October 1, observed globally as the International Day of Older Persons, is more than a date on the calendar. It is a call to conscience — a reminder of our shared responsibility toward those who once carried families, institutions, and communities on their shoulders. With medical advances and rising longevity, more people today are living longer — but not necessarily better. The quality of life in old age remains deeply uneven, marked by isolation, fragile community networks, and limited access to affordable healthcare.

Aging with Dignity: Beyond Years and Stereotypes

Aging is far from decline. It can be a period of wisdom, reflection, and meaningful contribution. Many older persons retain sharp intellect and discernment, yet are often sidelined by social stereotypes and shrinking family networks. The real challenge is not old age itself, but how society chooses to engage with it. What the elderly need most is belonging — spaces to share, participate, and thrive within community networks that value their experience.

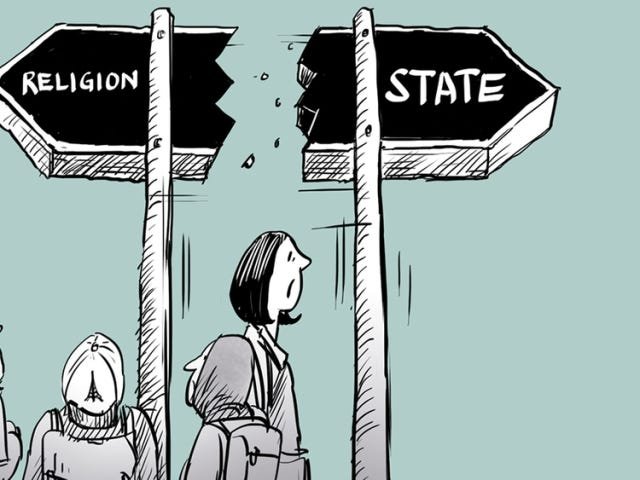

India has seen a growing number of retirement homes and assisted living centres, often modelled on Western designs. While these serve an important role, they cannot replace India’s long tradition of family and community care. Our cultural ethos — captured in the phrase Matha, Pitha, Guru, Daivam (Mother, Father, Teacher, God) — celebrates elders as the moral and emotional anchors of society. Yet these values have not fully translated into modern policy or practice.

It is time to reimagine elderly care through our own cultural lens. Instead of institutional isolation, we need community-driven models: senior co-living spaces linked to local temples, churches, or social clubs; intergenerational programs connecting youth volunteers with older residents; and neighbourhood health networks where retired professionals can both receive and provide services.

Turning Experience into Enterprise: Empowering Seniors through Startup Grants

Beyond care, the elderly deserve meaningful opportunities to contribute and remain active participants in society. Experience is a form of capital that cannot be replicated, and it can drive innovation, mentorship, and leadership. India could introduce robust employment incentives for firms that hire senior citizens — not merely as consultants or supervisors, but across roles where their expertise and insight genuinely add value.

Equally important are small business and startup schemes tailored for seniors. Supported through CSR initiatives or government-backed Senior Enterprise Funds, these programs can convert decades of knowledge into entrepreneurial ventures, creating economic opportunities while fostering dignity and independence.

Policy attention must also extend to those outside the formal system — the vast majority who spent their careers in private firms, charitable institutions, or informal sectors without pensions or insurance. These individuals form the invisible backbone of India’s workforce yet face the sharpest neglect in later years. Ensuring they have access to resources, training, and financial support is not just policy — it is justice.

The Fragility of Care: Insurance, Policy, and Moral Gaps

One of the biggest challenges facing India’s elderly is access to medical coverage. According to NITI Aayog’s 2024 report, Senior Care Reforms in India, 75% of seniors live with one or more chronic diseases, yet only 31% have any health insurance. This means nearly seven out of ten older citizens lack financial protection for even basic medical care. For many, insurance is more a gamble than a safeguard. Policies are full of exclusions, co-pay clauses, and hidden conditions that leave the very people they are meant to protect stranded in times of need. Many retirees experience coverage that is conditional, partial, or arbitrarily restricted — an irony in a system meant to provide care. What should be a guarantee of security has, for too many, become a risky bet against age itself.

Health insecurity compounds the problem. Despite schemes like Ayushman Bharat’s Vay Vandana card, offering up to ₹5 lakh in coverage for seniors, implementation remains patchy. Many private hospitals decline to accept these cards, even for chronic or terminal illnesses, particularly in Kerala. Private insurance for senior citizens remains prohibitively expensive — and often inaccessible once they cross sixty.

I have seen this up close. When my father passed away at 64, some seventeen years ago, my mother — then 62 — suddenly became ineligible for any new medical insurance. Her existing coverage, tied to my father’s employment, was withdrawn upon his death because widows were not included. My father had served as a Priest in a Kerala Church for nearly four decades, yet his institutional insurance vanished overnight. For an organization that often celebrates its legacy of service, the denial of even basic post-retirement medical support to long-serving employees’ widows reflects a profound failure of social responsibility — a quiet but serious departure from principles of fairness and justice.

Later, when we managed to secure private coverage — the only insurer offering late-entry policies for the elderly — the company became unreachable during a claim process. It was a silent betrayal, repeated for thousands of elderly Indians every year. The situation became even more painful when my mother was recently diagnosed with a critical health condition requiring long-term treatment. Such experiences reveal how fragile and exclusionary our systems remain, particularly for those outside formal employment.

Rethinking Elderly Support: Community, Contribution, and Rights

Elderly healthcare must no longer be treated as a commercial segment. It requires a dedicated regulatory framework with strong consumer protection, mandatory claim timelines, and strict penalties for unjustified denials. Healthcare for the elderly must be recognized as a public good, not a market commodity.

The moral neglect extends beyond the market. Many charitable and faith-based institutions — often exempt from formal welfare laws — fail to provide even minimal post-retirement support to long-serving staff, especially in matters of healthcare. Legal reforms should bring such organizations under welfare provisions similar to private companies, including pension and widow support. Income tax exemptions for non-compliant institutions should be reconsidered. Compassion begins at home; institutions that preach service must first practice justice.

Globally, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has long affirmed old-age social protection — including continued access to healthcare — as a fundamental human right. ILO Convention No. 102 and Recommendation No. 202 call for universal coverage, income security, and medical protection in old age, irrespective of occupation or employer type. Countries such as Japan and South Korea have integrated these principles into national frameworks, designing pension and health insurance systems to provide lifelong coverage and ensuring citizens do not lose protection upon retirement or widowhood. Aligning India’s social security laws with such global standards would ensure that every worker — whether in a factory, temple, or NGO — retires with dignity, health security, and assurance of care in later years.

To conclude, our elderly deserve more than ceremonial speeches or senior citizen clubs. They deserve systems that value their experience, protect their livelihood and savings, promote senior citizen startups, ensure their health, and uphold their dignity. As India moves toward becoming an aging society, we must build an ecosystem that integrates healthcare, insurance, livelihood, and community participation.

The measure of a nation’s progress is not how it rewards the powerful, but how it safeguards the vulnerable — especially those who once built the foundations on which we stand today. Translating these values into law, policy, and community practice is not optional — it is a test of our collective conscience. Policymakers, institutions, and communities must come together to ensure that India’s elders do not merely survive their later years, but thrive with dignity, security, and purpose.